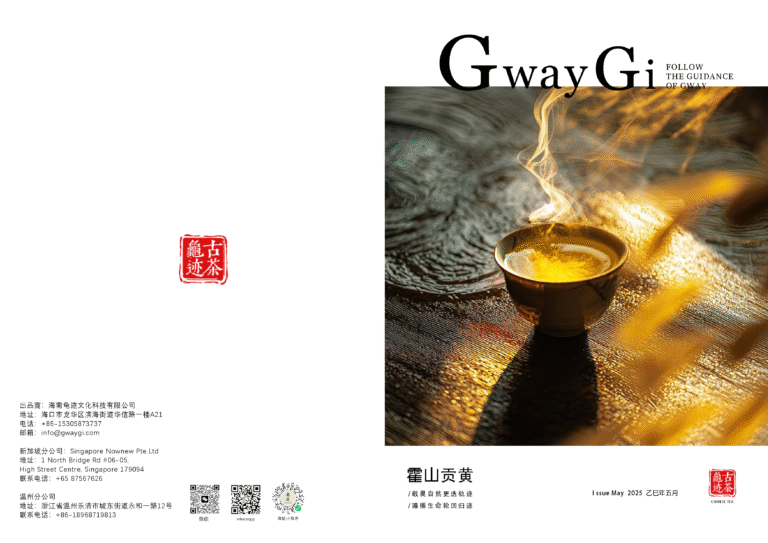

Are you tired of the grassy, sometimes bitter edge of green tea? Many tea lovers seek a smoother, deeper flavor profile. Chinese Yellow Tea offers a uniquely mellow taste and embodies ancient Chinese wisdom.

Yellow tea is one of China’s rarest and most complex categories, distinct from green tea due to the crucial “Men Huang” (Sealed Yellowing) process. This extra step removes the vegetal bitterness and results in a uniquely smooth, sweet, and gentle brew that supports digestion and a calm mind. I believe this brew is a perfect reflection of our “Walk Steady, Go Far” philosophy.

For years, yellow tea was an imperial secret, virtually unknown outside of China, and often mistaken for green tea by those who did find it. But it is much more than just a yellow-colored green tea. We must understand the profound, time-consuming process behind it. This slow craftsmanship reveals a unique story, especially in a specific variety like Huo Shan Yellow Bud.

Yellow tea, once a “golden tribute tea” exclusively enjoyed by emperors, was considered the “drink of gold and jade” reserved for royal use.

The Vanishing Emperor: Why Did Huo Shan Yellow Bud Disappear from History?

Why is Yellow Tea so rare today? This exquisite tea category takes incredible skill and time to produce. Its historical rarity is tied directly to its imperial, tribute-grade status.

Yellow tea is the rarest tea category in the world because its complex, labor-intensive production takes multiple days of hands-on work. For centuries, varieties like Huo Shan Huang Ya were reserved as a tribute tea for the imperial court. This exclusivity is one reason its history and production methods were largely lost.

I have dedicated myself to exploring these ancient traditions. I believe the story of Huo Shan Yellow Bud, or Huo Shan Gong Huang , teaches us about the true value of slow progress. Historically, this tea was considered a tribute tea in the Ming Dynasty. However, records of its production mysteriously stopped toward the end of the Qing Dynasty in the late 1800s. This gap in history shows us the fragility of true craftsmanship in a changing world. It requires a dedicated commitment—a steady pace—to keep such delicate art alive. The meticulous plucking of only one bud, or one bud with one or two tender leaves, sets the stage for a truly noble tea. This level of precision is the opposite of fast-paced industrial production. It is why we at GWAYGI honor this tradition. We see the rediscovery of this tribute tea as a reconnection to a more intentional way of life. The flavor is a reward for patience, offering a subtle nutty undertone and light sweetness.

I have dedicated myself to exploring these ancient traditions. I believe the story of Huo Shan Yellow Bud, or Huo Shan Gong Huang , teaches us about the true value of slow progress. Historically, this tea was considered a tribute tea in the Ming Dynasty. However, records of its production mysteriously stopped toward the end of the Qing Dynasty in the late 1800s. This gap in history shows us the fragility of true craftsmanship in a changing world. It requires a dedicated commitment—a steady pace—to keep such delicate art alive. The meticulous plucking of only one bud, or one bud with one or two tender leaves, sets the stage for a truly noble tea. This level of precision is the opposite of fast-paced industrial production. It is why we at GWAYGI honor this tradition. We see the rediscovery of this tribute tea as a reconnection to a more intentional way of life. The flavor is a reward for patience, offering a subtle nutty undertone and light sweetness.

Huo Shan Huang Ya: Tribute Status and Rarity

| Feature | Green Tea (General) | Huo Shan Huang Ya (Yellow Tea) | GWAYGI’s Philosophy |

| Historical Status | Widely consumed by commoners. | Tribute tea for emperors only. | Steadiness (稳): Quality over quantity. |

| Rarity | Abundant production globally. | One of the rarest teas globally. | Longevity (寿): Sustaining ancient craft. |

| Harvest | Various pluck standards. | One bud or one bud/one leaf only. | Gradual Progress (循序而进): Meticulous attention to detail. |

The Secret of ‘Men Huang’: How Does ‘Sealed Yellowing’ Remove the Green Tea Grassiness?

Why do people confuse yellow tea with green tea? Both teas share similar initial processing steps. The secret is the extra “Men Huang” step that transforms the flavor profile completely.

Yellow tea processing only differs from green tea through the addition of one extra, crucial step called “Men Huang,” or “Sealed Yellowing.” This process involves wrapping the warm, moist tea leaves in paper or cloth for up to three days. This “sweating” step encourages gentle, non-enzymatic fermentation, which naturally removes the grassiness of green tea.

When I look at the Men Huang process, I see our brand philosophy of “slow down, settle down” in action. First, the leaves are quickly pan-fired, a “kill-green” step, but usually at a lower temperature and shorter duration than for green tea. This preserves the tea but keeps some moisture trapped inside. This trapped moisture is essential for the Men Huang process. The leaves are then wrapped in thick flat packets—sometimes with paper, sometimes with cloth—and slowly heated over charcoal. This warm, wet, and enclosed environment allows the leaves to oxidize gently, turning a characteristic golden hue. The key is balance.

When I look at the Men Huang process, I see our brand philosophy of “slow down, settle down” in action. First, the leaves are quickly pan-fired, a “kill-green” step, but usually at a lower temperature and shorter duration than for green tea. This preserves the tea but keeps some moisture trapped inside. This trapped moisture is essential for the Men Huang process. The leaves are then wrapped in thick flat packets—sometimes with paper, sometimes with cloth—and slowly heated over charcoal. This warm, wet, and enclosed environment allows the leaves to oxidize gently, turning a characteristic golden hue. The key is balance.  The tea master must precisely control the temperature and humidity over the days it takes. This slow, deliberate transformation changes the chemical structure of the leaves. It decreases the chlorophyll content that causes the green color and grassy taste. In its place, the tea develops a soft, nutty, and exceptionally smooth character that is easy on the stomach. This is true mastery—not rushing, but allowing time to perfect the result.

The tea master must precisely control the temperature and humidity over the days it takes. This slow, deliberate transformation changes the chemical structure of the leaves. It decreases the chlorophyll content that causes the green color and grassy taste. In its place, the tea develops a soft, nutty, and exceptionally smooth character that is easy on the stomach. This is true mastery—not rushing, but allowing time to perfect the result.

.png)